- Home

- Sam Siciliano

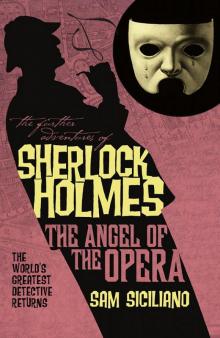

The Angel of the Opera Page 10

The Angel of the Opera Read online

Page 10

With his usual exquisite sense of timing, the Viscount regained consciousness almost at the door of the inn. Once inside, I found a bottle of brandy and made him drink some. I also forced him to eat some bread and cheese, all the while lecturing him upon the dangers of consumption and pneumonia.

Five

Early the next morning, while I slept late, Holmes returned to the churchyard. From the tracks in the snow he could discern that the violin player had been hiding behind the ossuary by the sacristy door and had fled through the church, then walked a mile to a waiting carriage. At Lannion, the clerk at the ticket office recalled a woman in black purchasing a ticket for the early express train to Paris. “Ugly, she was very ugly, from what I could see of her face behind the black veil, and tall, very tall.”

Sherlock smiled as he related this. “A clever disguise, Henry. I have done the same thing on occasion, but my height also makes such a charade difficult to pull off.”

After the primeval gloom of Brittany, Paris with all its present-day splendors (especially modern plumbing and readily available hot water for bathing) was even more welcome. Although my family was not poor, neither were we wealthy; hence it was an unaccustomed pleasure to stay in one of the finest hotels and to sup at the best restaurants in a country where food was truly appreciated. The French and English have their strengths and weaknesses, but when it comes to cuisine, the tricolor utterly vanquishes the Union Jack.

We returned on Monday evening, the opening of Faust scheduled for the following Saturday. Early Tuesday morning Holmes went to the Opera and asked the managers if they possessed any architectural plans or writings about its construction. By way of reply, they took him to a large room which served as the Opera library. The original architectural drawings were there, along with photographs, books, and stacks of newspapers containing articles about the building, performances, and singers. Holmes went at once to Garnier’s own memoirs, Le Nouvel Opéra. He lit his pipe, opened the first volume with his long thin fingers, and told me to go enjoy the city.

The winter sun being bright and cheery, I decided to visit La Tour Eiffel, which had been finished the year before for the exposition. I was not greatly impressed, but had a pleasurable time all the same. However, in my solitude, my thoughts often turned to Michelle.

Holmes spent a long day sequestered in the Opera library, then another day visiting old haunts about the city and questioning various people. He did not have so large a network as in London, but he had worked in Paris enough over the years to have contacts at the various social strata. Among them were a second-rate poet living in a garret in Montmartre who knew all the talk of the Bohemian world, an inspector of the French police whom Holmes had helped with several cases, an elderly nobleman whose daughter he had saved from a notorious rake, and a pickpocket who frequented all the markets and would do anything for a few francs. Holmes also called upon Madame Giry.

Sherlock told me about them all at dinner that night. He was frustrated with his interviews. “Everyone in Paris knows of the Viscount’s sudden infatuation with Christine Daaé. Take your choice. She is either an innocent girl and brilliant artist being pursued by an aristocratic libertine, or she is a calculating little vixen skillfully reeling in the sweet but gullible Viscount. Everyone has heard something of le Fantôme, and there are a variety of ingenious tales involving him, Carlotta, Christine Daaé, and Joseph Buquet. Buquet’s death is widely attributed to the Phantom.” He wiped at his mouth with a napkin, then sat back and shook his head as the waiter approached his glass with the wine bottle.

“And what of all your reading in the library?”

“Ah, there things were rather more interesting. I remained at the library until two this morning. Garnier is something of an egoist, but his narrative constantly refers to a Monsieur Noir who was involved in every phase of the construction, a true jack of all trades, builder, designer, carpenter, contractor. Near the end of the memoirs Garnier finally acknowledges his dept to Monsieur Noir and mentions his ‘affliction tragique.’”

“And what was the nature of this tragic affliction?” I asked.

“He does not say, but he thought it almost a blessing that Monsieur Noir had died.”

“And how did he die?”

“Garnier does not say, but it happened even as the construction was being finished.”

“Oh, I forgot to tell you: de Chagny came to the hotel this afternoon looking for you. He has received a note from Christine Daaé saying he must not see her again, for his own safety.”

“Indeed?” Holmes took out a cigarette. “If I missed the Viscount, then the day’s travails were not totally in vain. Friday I shall meet with the managers, and they will demand an answer to their problem. Enjoy the wine, Henry; we may soon be forced to sample a cheaper vintage. I have a few threads, nothing more.”

The next day Holmes wandered about the Opera while I tried to keep up with him. In the morning we traipsed about the upper cellars, the two subfloors just below the mammoth main stage. What a labyrinth! Theseus himself would be confounded. At one point we watched men turn various wheels; ropes creaked; machinery ground in the distance; and overhead a trap door opened, Mephistopheles rising slowly upon a platform.

In the afternoon Holmes visited the upper regions over the stage. I let him talk me into accompanying him partway this time, and I was soon sorry. We went up the stairs past three or four of the metal catwalks. I gazed past the rail and saw the vertical lines of literally hundreds of ropes, some supporting long iron pipes to which flats could be attached. Dimly I heard voices from below and made the mistake of looking down. The vertigo was upon me at once. My chest seemed to constrict, my hands turned to ice, and I began to sweat profusely. Telling Sherlock I could endure no more, I started down, keeping my eyes always fixed straight ahead.

That night I had dreadful nightmares. Insubstantial catwalks quivered over great depths; instead of the stage being below, there was only darkness, eternal darkness. At last I fell, plummeting downward into the abyss. I woke up in a cold sweat and could not fall back to sleep for some time.

The next morning I was in poor spirits, and joining Holmes for his interview with Madame Carlotta did not help matters. A very disagreeable hour it was. If I had had any doubts about Christine Daaé’s appraisal of her rival, Carlotta dispelled them. A large woman in her late fifties, she seemed a likelier Valkyrie than a Marguerite. Her hair was an incredible shade of red, her cheeks were heavily rouged, and she wore a white dressing gown with a silvery fur collar. Her companion was a surly little white cur who constantly barked or snarled; both his yellowish teeth and his diminutive size made him resemble a rodent more than a canine. The dressing room was at least three times the size of Christine’s.

The mention of Miss Daaé’s name was enough to launch a lengthy diatribe against the young singer. She was too small and too stupid to sing well; she had no high notes, a poor middle range, and weak low notes as well; she had returned Carlotta’s kindness and generosity with malice; she and her supporters were capable of any villainy; the Phantom did not exist, but was only a device dreamed up by the increasingly desperate Daaé, etc., etc. I found myself growing rather warm at such a display of bile, but Holmes was at his most polite and charming. She showed us the threatening notes she had received. The clumsy hand and red ink we recognized at once.

“I agree, Monsieur Holmes, with Messieurs Moncharmin and Richard on this matter. One can never yield to petty threats. My admirers deserve better.”

Holmes gave a rather noncommittal shrug. “I shall be discussing the situation with those gentlemen this afternoon.”

He had made the mistake of introducing me as Docteur Vernier. Madame Carlotta begged that, as her own personal physician was indisposed, I might examine her throat. Despite the irritating letters and the ingratitude of Mademoiselle Daaé, she felt quite well, but one could never be too careful. I concealed my reluctance, placed her where the light was best, then peered down the gaping maw of her mouth

. All was pink, moist, and healthy. I considered giving an ominous groan and diagnosing an incipient infection, but professional responsibility got the better of me.

When we left at last, I muttered, “A truly unpleasant woman.”

Holmes laughed. “I am glad I did not have to look down her throat. Yes, unpleasant, but it is these great unfeeling brutes who manage a career of thirty or forty years. The romantic ones like Christine Daaé burn out like shooting stars, consumed by their own fires, while the oxen such as Madame Carlotta plod monotonously onward. It is one of the tragedies, the paradoxes, of music, of art. You will never see Madame Carlotta lose a good night’s sleep over anything–or miss a meal, either.”

Later that afternoon we visited the managers in their office.

Richard lit a cigar and folded his burly arms. “Well, Monsieur Holmes, what have you to tell us? Tomorrow night is the performance of Faust, and we have received yet another note.”

Holmes glanced at it, grimaced horribly, then laughed and handed me the paper. “This Phantom is remarkably clever for a shade.”

The note was briefer than the others: “Mr. Sherlock Holmes will not be of any assistance to you or Madame Carlotta should you defy my wishes. The curse remains. Ignore it at your peril.”

“So what are we to do, Monsieur Holmes?” Moncharmin peered at him through his monocle, that eye appearing larger and resembling that of a fish in a glass aquarium.

Holmes walked to the window and leaned against the sill, his back to us. Richard scratched at his white beard and puffed his cigar. Finally Sherlock turned. “Gentlemen, I am afraid that I must counsel you to yield to the Phantom’s demands.”

Moncharmin’s monocle popped out of his eye.

“What!” Richard roared.

“Please hear me out, gentlemen. Let me first dispel a common misconception: I am not, Doctor Watson’s writings to the contrary, a magician. All of my cases are not miraculously resolved in a day or two. In this instance I require more time. I have been in Paris little more than a week.”

“But we do not have all the time or the money in the world!” Richard exclaimed. “Have you discovered nothing? The best you can do is tell us to pay this blackmail? It’s outrageous! I...”

Moncharmin placed his hand over his partner’s wrist. “Let us listen to what he has to say.”

Holmes nodded. “Thank you. Gentlemen, the difficulty with this case lies in the Opera itself, this incredible edifice surrounding us. You told me it was foolish to think I could tour it in a day or two. You were correct! This is a world unto itself, a miniature cosmos with its Heaven above and Hell below. The difficulty is compounded by the opponent we face. I sense a genius at work, one so far turned toward evil. This genius, I have no doubt, has spent many years in the Opera; most likely he has dwelt here since its completion in ‘75, some fifteen years ago. Many of your older employees have told me the Ghost has been here from the earliest days. The Phantom must know every corner of the Opera, above and below ground–every room, every attic, every closet–the lake underground and the mazes of rope and steel above and below the stage. This knowledge is the source of his power and the very real threat he presents. I will continue my efforts, but I urge you to comply with his demands until I can discover more. I know what your annual budget is; the sum he demands is a pittance, as your predecessors realized.”

Moncharmin began to tap nervously at the desk. “This is unacceptable, Monsieur Holmes.”

“Outrageous, as I said before!” Richard’s face was even redder than usual. “We shall not pay this blackmailer one franc.”

“Then, Messieurs, you and you alone will be responsible for the consequences.” Holmes voice was cold and soft.

“Consequences be damned!” Richard exclaimed.

Moncharmin placed his monocle back over his eye. “To what consequences do you refer?”

Holmes placed his hands on the edge of the desk and leaned forward, causing Moncharmin to instinctively draw back. “Let me be frank, gentlemen. In all my years as a consulting detective I have never seen a greater disaster waiting to happen. Do you have any idea what even one clumsy saboteur could do during a performance? And I very much doubt the Phantom is clumsy.”

“Surely you exaggerate, Monsieur Holmes.” Moncharmin withdrew his handkerchief from the pocket of his frock coat.

“Do you wish me to spell things out? You have hundreds of meters of gas lines running everywhere; an accidental fire would be simple to arrange. Scenery could fall and injure one of your principals, such as Madame Carlotta, or a trap door could unexpectedly open, swallowing her up. You have many high balconies from which an accidental fall could occur. There are chandeliers and heavy statues everywhere__”

“Enough... enough...” Moncharmin moaned, wiping his forehead with his handkerchief.

Richard hit the desk with his right fist. “He’s trying to frighten us! Just whose side are you on, Holmes?”

Sherlock stood up straight and stared back. “And what do you mean by that remark, Monsieur Richard?”

“You know damned well what I mean! It’s bad enough charging us so ridiculous a fee, but then you stand there and practically threaten us!”

Holmes put on his gloves, tugging at each one fiercely, then picked up his overcoat, his top hat, and stick. “I can see my services are no longer desired. Gentlemen, I wish you the very best of luck in your endeavors at the Opera.” His voice shook slightly.

“Please, Monsieur Holmes. You must understand our position!” While Richard had grown redder and redder, Moncharmin had grown paler. “There is Madame Carlotta to think of–and all that money...”

Richard shook his head. “We will not pay a franc, not a sou. The Ghost be damned!”

Holmes gave a ghastly smile and raised his hat. “Very well. Good day to you, gentlemen.”

“Monsieur Holmes...” Moncharmin groaned, while Richard glared on.

Holmes strode off, his walking stick angrily tapping at the floor. We marched along the grand foyer beneath its painted vaults and crystal chandeliers, gilt surfaces glittering all around us, then we went down the grand stairway. The vast spaces, the gaudy splendor of all that marble, wood, bronze and gold, suddenly seemed ominous to me, cold and inhuman. I was relieved when we stepped outside into the open air.

I shook my head. “I think of myself as a fairly intelligent man, and I have followed you all about the Opera House. However, the idea of sabotage never even occurred to me until you mentioned it just now. How could I have failed to...?”

“Yours is not a deranged mind, Henry. Nor is mine, I hope, but I have long practiced thinking like my opponents.”

“Dear God, they should have listened to you! The place is a powder keg, a disaster waiting to happen.”

“Calm down, Henry.”

“All those gas lines! What a fire it would... Do you think the Phantom would harm innocent people?”

“I do not know. I do not know. I would like to think that our Angel of Music could not, that a being capable of such music was beyond petty malice, but the honest truth is that I do not know. I have had more proofs of man’s bottomless capacity for evil than I care to remember.”

“But what can we do?”

Sherlock smiled wearily. “That was my problem–that was why I told them to humor their Ghost. The Opera is too large a territory to attempt to guard. How could they protect against every possible threat? They would need as many policeman as spectators. Of course, they expect the great Sherlock Holmes to know exactly where the Phantom will strike. Watson be damned! They all require a magician–a sorcerer! I must wrap up the case in a day or so with a few clever deductions, and...”

I smiled. “Calm yourself.”

He shook his head angrily. “I will not calm myself. It is insufferable, intolerable!”

“Now you sound like Monsieur Richard. If it were not for Watson, you would not have received a thousand francs a day.”

“Much good it does me if they are not wil

ling to keep me on the case. Christine Daaé is the key, I am certain. If I had more time I would next turn my attention to her.”

“What shall we do now?”

“Eat an especially fine meal, as it has been a strenuous week, attempt to get a good night’s sleep, and attend the performance of Faust tomorrow evening. Wild horses could not drag me away from le Palais Garnier tomorrow. I doubt the managers will bar us from the box reserved for our use. We shall be on the grand tier and not too distant from Box Five.”

“Do you think...? Will it not be dangerous?”

“Certainly.”

I wished for some of his sangfroid.

When we arrived early the next evening, a great throng of humanity crowded the grand stairway. All the multicolored raiment, the movement, the rumble of that chorus of voices, transformed the stairway; the mood of the place was completely different. Gone was that ominous, brooding silence I had sensed the day before.

The spectators rivaled the Opera in their splendor, especially the women. The men wore one of two costumes. The usual formal wear included a black coat, top hat, trousers, and waistcoat with white shirt, gloves, and bow tie. The second type was a uniform with the gaudy ostentation at which the French excel: tight white or scarlet trousers, shiny black boots, and a jacket of bright blue or darker navy covered with gold buttons, braid, and epaulets. The women were allowed more variation: their dresses were of every color; and the blazing light from the gas lamps glittered upon the diamonds, rubies, emeralds, gold and silver of their jewelry. The gowns of the younger and more daring revealed white shoulders, throats, and décolletage, but all the women wore long white gloves rising midway between shoulder and elbow.

Along the stairway, members of the Republican Guard stood stiffly at attention, their silvery helmets polished mirror bright, gaudy red plumes sprouting from the tops. I passed one young guard whose neatly waxed black mustache had pointed ends at least two inches long.

The Web Weaver

The Web Weaver The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes--The Devil and the Four

The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes--The Devil and the Four The Moonstone's Curse

The Moonstone's Curse The Angel of the Opera

The Angel of the Opera The Grimswell Curse

The Grimswell Curse The White Worm

The White Worm